By Anderson Isiagu, May, 2019

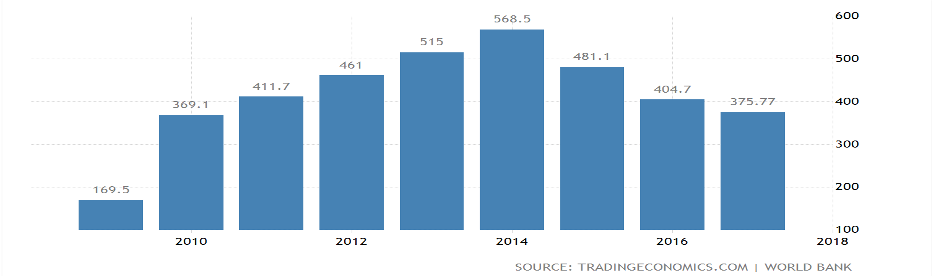

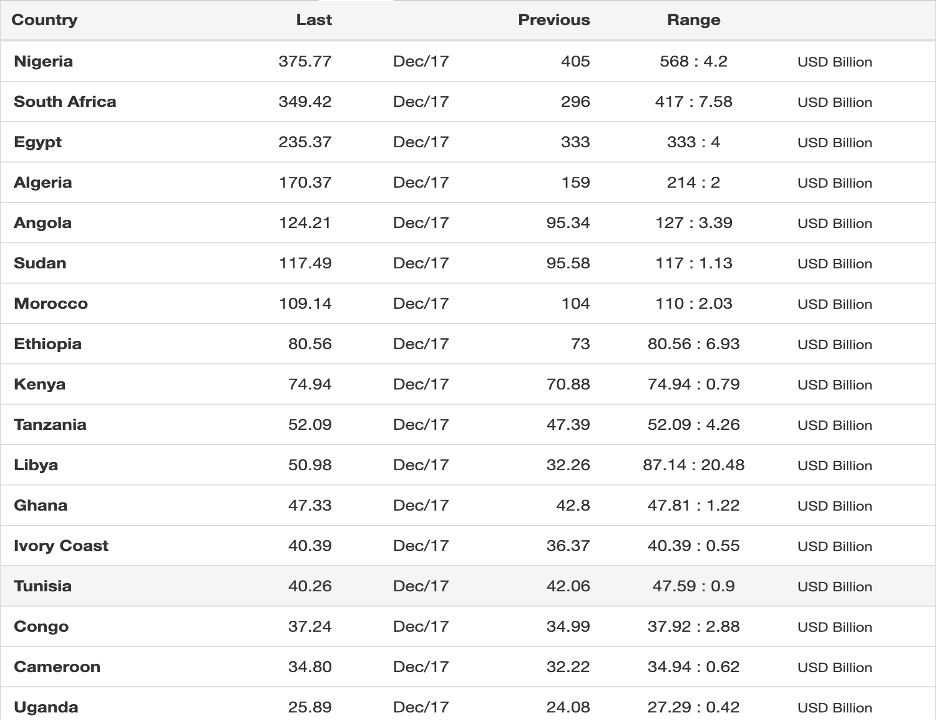

INTRODUCTION According to data from the World Bank, the Nigerian economy boasts of having the largest gross domestic product (GDP) in Africa. The GDP growth between 2006 and 2016 was around 5.7% per year. In the second half of 2017, economic growth rate was pegged at 1.0% and this was driven mainly by the oil and gas sector, agriculture, and the impact of private sector investment. Private sector activities, along with many other government-based structural reforms indicate that globalization is actively at play. There are over one hundred multinational corporations (MNCs) and transnational organizations actively operating in Nigeria. These corporations are diffused across different sectors of the economy including oil and gas, telecommunication, health and wellness, consumables, and automotive. Among the top forty MNCs oil companies such as Shell, Chevron, Mobil, and Total make up the top four. Nonetheless, in spite of the presence of these corporations and the huge contribution they make to the GDP, Nigeria’s economic indicators do not conjure up confidence. According to data from a 2016 Gallup Economic Confidence Index, Nigeria economic confidence has been on a downward decline from 6, in 2008, to minus 45 in 2016. Nigeria was ranked 18 out of 19 countries in Africa. Unofficially, Nigeria has been dubbed the ‘Giant of Africa,’ but available economic data does not support or confirm the validity of such moniker. In this paper, I will trace the historical and contemporary forms of regionalization and globalization that are at play in Africa, using Nigeria as a case study. The paper will seek to unearth some of the policies that are globalization friendly, or lack of one. I will delve further into the role and impact of globalization in the impoverishment or improvement of the lives of Nigerians and their economy. Considering that the agitation of hyper-globalizers is geared towards the total freedom of the market from government control, it would be apt to embark on a fact finding survey of government policies that will help to determine if Nigeria has engaged in any form of liberalization and free market policies in the bid to determine their impact. An assessment of the impact, intensity, extent, and velocity of the forces of globalization will be carried out in the bid to determine the effect they may have had on the rate of poverty or prosperity and infrastructural development. Finally, the paper will examine the overall effect of globalization on human dignity and solidarity in Nigeria. A. STRATEGIC POSITION OF NIGERIA IN AFRICA Nigeria is the world’s most populous black nation and it has the largest GDP in Africa as of 2014. With a population of over 190 million people, Nigeria has been known, in both formal and informal circles, as the “Giant of Africa.” In the words of professor Patrick Loch Lumumba, a renowned Kenyan human rights activist, “When Nigeria gets it right, Africa also gets it right.” Lumumba holds that when Nigeria sneezes, Africa catches cold; a position that underscores the strategic position of and role played by Nigeria in the continent . Nigeria has played important leadership roles throughout the African continent in various capacities since becoming independent from the British Colonial empire in 1960. Its GDP has averaged $97.52 billion between 1960 and 2017, peaking to $568.5 billion in 2014. In spite of falling to $375.77 billion in 2017, Nigeria’s GDP still represents Africa’s largest. By virtue of the social and economic implication of a large population and huge GDP (powered by a single commodity-oil) Nigeria has exerted its influence around Africa both economically and politically. and

According to the Chronicle, an online Nigerian newspaper, there have been many instances in history that solidified the important position of Nigeria. Nigeria actively supported several African states such as Angola and Zimbabwe, as well as South Africa. In the case of South Africa, the government of Nigeria established a financial assistance scheme tagged “South Africa Relief Fund” in 1976. This fund provided various forms of support to black South Africans who were marginalized and victimized under Apartheid. Other forms of financial support included a $5 million annual provision to the Africa National Congress (ANC) and the Pan African Congress (PAC). Nigeria provides electricity to neighboring countries like Benin Republic and Chad at affordable rates. It is no wonder why economic downturns in recent years have also had adverse effects on neighboring African countries and the rest of the continent. In 2016, the president of Benin Republic, Patrice Talon noted that other African countries suffer due to Nigeria’s inability to use its potentials. He made this remark when responding to Nigeria’s failure to supply Benin with electricity like it has always done. Electricity production, which has remained largely epileptic, is dependent on hydro power and gas. Nigeria’s gas pipelines have been the target of militancy in recent past, who bombed them in their bid to seek greater autonomy and resource control policies in the oil-rich Niger Delta area of the country. The ripples of any crisis that hits Nigeria, with its consequent economic, social or political implications are felt by the rest of Africa. According to Talon, “The crisis hitting Nigeria is what is hitting us.” There is no doubt that Nigeria is to the rest of Africa as America is to the rest of the world, and a basic understanding of this strategic position would help in determining the nature and extent of African interconnectedness. B. GLOBALIZATION AND AFRICA What exactly is the nature of globalization and what are the parameters upon which to gauge its impact, extent and velocity in Africa? Prominent authorities in the field of globalization have written extensively on the subject. However, all the empirical evidence to support globalization is ubiquitous and mostly centered around the United States, Europe and most of the developed world. While there exists numerous mention of the impact of globalization on poor African countries and the effect of capitalist economies and their imperialistic tendencies, there is a dearth of information that better represents the exact nature and precise extent of globalization, as well as its impact in Africa. Notwithstanding, it is plausible to use the wealth of data gathered from probes into global interconnectedness, one that is centered around the Western world, in the measurement of the nature, velocity, extent and impact of globalization in Africa. Only this time, such a study would take into account African values and worldview. Different scholars may differ in their representation of the nature of globalization, but they are unanimous in the conceptual premise upon which they arrived at a definition of globalization. According to David Held, “globalization… is neither a singular condition or a linear process.” Building upon this central background, Held gives a simple definition of globalization as the deepening, widening, speeding up, and strengthening of global interconnectedness in all facets of life. This definition is limited and does not shed light on the scope or far reaching effects of globalization. Also, it is insufficient to base a probe into Africa’s response to an increasingly interconnected world on such a definition. Held then takes the concept further by presenting a more comprehensive and multifaceted definition: “A process (or sets of processes) which embodies a transformation in the spatial organization of social relations and transactions- generating transcontinental or interregional flows and networks of activity, interaction and the exercise of power.” The definition above takes into account the intercontinental and transnational nature of globalization and how it is turning the world into a small global village, the activities that provide recognizable traits with which to identify the effects, as well as the actors and the powers they wield. It is true that the principal actors in this process are mostly the US and the rest of the developed world and this leads one to wonder if globalization is not Westernization in disguise. If this is the case, conservative Africanists would reject globalization in any form in order to prevent the adulteration of African cultures, beliefs and customs. Such effects would present Afrocentric groups and agitators with a rallying cry upon which to advocate for protectionist policies that are meant to curb the effect of Westernization in the form of globalization. The Western world has always made inroads into Africa via trade since the colonial era and this seems to still hold true today. Hyper-globalizers, according to Held, maintain that a globalized world would bring immense economic prosperity and an increase in the quality of life of its participants. Skeptics, however, do not hold the same view. There also exist Transformationalists, who advance the transformation and evolution of cultures, institutions, and human interactions as the product of globalization. An important factor in the processes of globalization is “profit.” Capitalists are in the forefront of a strong and intense advocacy for the liberalization of the world economy, which would lead to an open and free market and provide access to more profit. Africanist may argue that globalization is a guise for Westernization, but in spite of the fact that hunger for more profit is a key propeller towards a globalized economy, big MNCs appear to be in a position of advantage because of their manufacturing power, access to technology, and wide reach. Africa on the other hand, as is the case with most poorer nations, are largely consumer states and as long as the status quo remains the same, Western and capitalist players will continue to have the upper hand. These MNCs and their operation in Africa would also continue to shape the economic policies of their host nations. Unfortunately, the original intent of such policies is to first favor the MNCs and the host nation second. This notion was supported by John J. Mearsheimer in his book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. He argues that the underdevelopment as well as exclusion of developing countries from the global economic system is because of the manipulation of institutions such as the IMF, WTO or the World Bank by MNC and transnational corporations into shaping the globalization agenda to favor their interests only . Using Nigeria as an example, I would now probe further into how globalization and its institutions have affected, shaped, and impacted, either positively or negatively, on the economy and quality of life of Nigerians, as well as the response of state actors to globalization. C. HISTORICAL LOOK AT THE NIGERIAN ECONOMY a. PRE-COLONIAL The Nigerian state has been engaged in some form of trade since before the incursion of any foreign entities. Early forms of trade were mainly carried out in local markets and village squares and they were mostly subsistence. Goods were also exchanged through another form of trade known as barter. The first sign of interconnectedness among West Africans was visible in trade relations that existed among distant West African settlements. Not only did Africans trade among themselves locally and regionally, they also did so internationally with Europeans underscoring the fact that some form of globalization has been at play in Africa long before post modern times. Sarah S. Berry noted that “West African peoples have a long history of international trade. Communities on the coast of West Africa exported slaves, ivory, gold, and other commodities to Europe and the Americas from the sixteenth century; before that, West African products were conveyed to North Africa and the Mediterranean by trans-Saharan caravans.” The nascent industrialization of the West created a high demand for raw materials. Turning to Africa to fill this vacuum led to a high demand for African goods and the consequent trade relations and colonization that followed. The Portuguese arrived in the late 15th century, followed by the British in the second half of the 19th century. An intricate trading relationship had existed among coastal dwelling West Africans and those in the hinterlands. Europeans took advantage of this arrangement that was on ground to promote trading relationship and gain access to a variety of African products. Africans in the coasts exchanged goods with those in the hinterlands while coastal dwellers exchanged such goods for European goods. This laid the foundation for the smooth running of the slave trade, which lasted from the middle of the 17th century to mid 19th century. Considering that Africa’s interaction with Europe brought about human suffering in the form of the transatlantic slave trade, the question then is if there were any benefits that came with such interaction. Also, was this really globalization as we know it to be today or a case of forcefully appropriating for themselves, the raw materials Africa was blessed with for the development of the West? David Northrup’s position seems to lean towards a number of ways African nations may have benefitted from the interaction with Europe when he suggested that “…the development of fishing villages to city states and their considerable wealth and power were largely dependent on their monopoly of trade with Europeans.” He went on to argue that the result of a growing volume of trade through local ports had an impact that stretched from the coast to the hinterland. Local markets around the region became more closely linked, communities with divergent political ideologies united around trade, merchants were exposed to more wealth, and there ensued, a new demand for European minerals and manufacturers. In addition to these developments, it is possible to understand the extensity of this Euro-West African interconnectedness by examining the commodities that were bequeathed to Africa. According to Richard Olufemi Ekundare, “the Portuguese introduced a number of new crops, including tobacco, rice, cassava, groundnuts, sweet potatoes, red pepper, guava, sugar-cane, oranges, and limes.” African countries, in addition to existing commodities, rode on these new crops to become economically relevant and competitive in the international scene. While it is true that Nigeria would later grow to become Africa’s largest groundnut exporter, the wealth that was created from this trade relationship, as Northrup clearly noted, rested in the hands of a few merchants. Hence, the cost of this link to human dignity, as perpetuated in slavery and the appropriation of Africa’s wealth, far outweighs its material benefits. A significant aspect of globalization includes the intermingling of or hybridization of cultures. This intermingling was evident in some of the developments that took place in the social, political, and economic realms. An example, as mentioned above, is the demand for African produce as well as the new crops that were introduced to Africa. Politically speaking, African regions gained their names from their trade relations with Europeans. According to Ekundare, the West African commodities that the Portuguese traded in, viz a viz ivory, gold, and pepper, affected the naming of the regions involved. The areas that traded in ivory became known as Ivory Coast, while those that traded in gold and pepper were known as the Gold Coast and Grain Coast respectively . This intermingling is responsible for the adoption of these foreign names by the locals. Furthermore, it would not be safe to assume that these regions did not go by a name that was indigenous to and known among the locals. However, such names do not have the same popularity around the world as their foreign counterparts do. b. Colonization and Post-Independence By virtue of the trans-Saharan and trans-Atlantic slave trade, coupled with diffusion of European and American culture in different parts of Africa, I am inclined to assert the notion that the contemporary concept of globalization is not a new phenomenon as far as Africa is concerned. Globalization, as Held puts it, is not a single process, neither does it take a single form. It could be economic, cultural, religious, ecological or military. In practice though, they may be interwoven and occurring simultaneously. Coming from this background, Africa’s contact with the West was first economic, religious, militaristic (imperialist), and cultural. Ekundare appears to suggest that the initial intent of imperialists, especially that of the Portuguese was not always about slavery. According to Michael Parenti, empires are not necessarily innocent, nor are their actions carried out by accident. They are calculated moves that are backed by vast allocation of financial and human resources sufficient for the partial or total take over of the natural resources of a people. They took the form of quests and explorations that turned different parts of the world, such as Africa, into trophies. As more and more imperialist nations found out about and took interest in the vast resources and raw materials that are found in Africa, this led to the “Scramble for Africa.” Competing European imperialists and their business interests were gearing more and more towards an armed conflict for the control of Africa. Instead, they opted for a more civilized settlement. The Berlin Agreement of 1885 saw to the balkanization of Africa, giving over the control of regions to European powers. This single move legitimized the colonization of Africa by Britain, Portugal, Germany, Italy, and France. Evidence from British colonial rule goes to confirm the assertions set forth by Parenti about the intentional and calculated actions of empires. The British government took on various projects that were supposed to bring about the institutionalization of governance structures, rule of law, social organization, and coherence. These reforms were meant to promote the interest of the British empire only and consolidate their hold on all business opportunities in Nigeria. Ekundare confirms this when he noted: The British government's efforts to establish good and orderly government in Nigeria in order to make it easier to exploit the country's natural resources took precedence over other economic considerations. However, by the end of the nineteenth century a rough basis for economic development had been initiated, as export production was being encouraged, and real attempts to build up the social and economic infrastructure of the country had begun. Frankly, the indirect result of the British’s attempt for control and consolidation came in the form of infrastructural developments. To take this at face value would be to ignore the calculated attempt of the British to put in place structures that would aid the smooth running of their businesses. Colonial rule was facilitated by companies; companies that played the same role MNCs play today. They were national, they had full monopoly, and they were backed by royal charters, with authorization to engage in merchant activities and administer the regions they controlled. The Royal Niger Company (RNC) oversaw British interests in West Africa, the East was administered by the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) while the British South Africa Company (BSAC) oversaw businesses in Southern Africa. These companies share common similarities with present day MNCs. Just like MNCs are known to set up shop in foreign countries with large buildings and skyscrapers, these royal colonial companies were forced to implement an infrastructural plan that bequeathed African cities with modern facilities. A diffusion of Western technological knowhow quickly spread, giving Africans access to innovations they would not have had access to. Lagos, Nigeria, is one of Africa’s biggest and most developed cities today largely because it is a coastal city that benefitted from colonial infrastructural developments. Another similarity is that MNCs are usually private institutions that are culturally alien to their host countries. They represent the interest of their original countries and are protected by their countries via international advocacy and policies. British colonial companies were run by private firms on behalf of the monarchy in England. c. Africa Interrupted Significant developments continued to take place locally as a result of the operation of British royal companies. Total consolidation meant going deeper into the hinterlands to access more trade routes and commodities and that meant better infrastructures. This led to the development of transport and communication infrastructures such as roads, railways, ports, postal, and telegraphic services. Under normal circumstances, such infrastructural developments would have elicited praise and a standing ovation for the British, but there is nothing normal about the ulterior motives with which Britain and other imperialist nations plundered Africa. It would not be out of place to argue that Africa’s experience with imperialist nations was both negative and somewhat positive; it depends on through which glass a spectator is looking. For ultra Africanists, who believe that Europe had no reason whatsoever for the occupation and plundering of Africa’s wealth, nothing good came out of that experience. Instead, Africa’s progress and development was set back for many years. Madeleine Scherer, drew up a list of very important possibilities that could have been if Europe did not colonize Africa. While some of them objectively point to the opportunities that Africa would have missed out on, she believes that Africa would have been strategically placed among some of the world’s richest and most prosperous nations. Scherer pointed out that “As a result of dependence on Europeans and civil wars and ethnic violence, all consequences of European colonization, African nations were not able to gain political and economic stability that would allow them to become world superpowers. Had African nations been given the opportunity to grow autonomously they could have achieved comparable levels of economic and political prosperity to the superpowers of the present world.” Simply put, colonization interrupted Africa and created the framework for a bulk of its present predicaments. To support the notion that Africa’s natural growth and development was interrupted, Joshua Dwayne Settles said, “The imposition of colonialism on the continent of Africa occurred for many reasons, not the least of which was economic. Prior to this development, Africa was advancing and progressing economically and politically. Colonialism encouraged this development in some areas, but in many others severely retarded the natural progress of the continent. Had colonialism never been imposed on Africa, its development would be significantly different and many of the problems that plague it today would not exist.” d. Nigerianization of the Economy After independence in 1960, Nigeria was left with a struggling economy that was not diversified. Its leaders would rally towards building a stronger economy around the agricultural, industrial and service sectors. Now, the structure that have been put in place by the colonial masters was such that it ensured that a constant stream of Nigeria’s wealth came to them directly or indirectly. Directly, meant via colonial appropriation. It took advantage of the same resources indirectly through its control of all the international machineries of trade and trade policies, an arrangement that ensured that products from Nigeria and the rest of Africa were purchased at close to nothing. In response to this development, the Nigerian government needed to retain resources and wealth at home and prevent them from going to Britain. It courted a brand of capitalism that allowed for state control and private sector participation. While government regulated the economy, provided infrastructures and enacted favorable laws, the private sector controlled the means of production, distribution, and exchange. This arrangement did not kick off as smoothly as the government had expected. The members of the private sector were not able to raise the huge capital that was required to build factories and maintain manpower. Until now, indigenous people had only been middle men in trade relations and were fenced so far away from the center of wealth that most people did not have the education or skills needed to fill the gap that was created by the exit of the British. In Toyin Falola’s account, “The economic objectives at independence were clear: the country would seek the means to transform its economy at a rapid rate, from a "backward" to a "developed" one. To attain this, it would expand its educational and social services, revise the plan document of the 1950s, and pump more money into the economy.” In essence, the government sort to improve the standard of living of Nigerians above and beyond what it was under imperial rule. This meant a robust economic turn around and diversification. Post independence transition to what became known as Nigeria’s first republic was marred by difficulties that were brought about by the lingering ghosts of colonialism. The first republic, a period of democratic rule, was short-lived and lasted from 1963 until it ended in a military coup in 1966. Both civilian and military government reforms repositioned the economy from one that was solely dependent on the export of cash crops to one that generated revenue from multiple sectors such as agriculture, foreign trade, industrialization, entrepreneurship, and revenue allocation (federating units remitted certain percentage of their revenue to the center). In 1971, Nigeria joined the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and was ranked as the seventh largest exporter of crude oil in the world. This opportunity generated enormous revenue that powered the economy. Between 1971 and 1974, an unexpected spike in international oil prices ushered in the ‘Oil Boom’ and Nigeria cashed in a windfall that had significant impact on the economy. This is a typical example of the impact of the forces of globalization. How so? Ripples caused by changes in global oil prices was felt by Nigeria, in this case, with positive outcomes. Evidently, Nigeria did not cause the spike in oil prices. It may have been the seventh largest exporter of oil at the time but it did not necessarily compete favorably with the top oil producing countries of the world. This is partly because it did not have refining capabilities, nor was it directly able to determine the price of its own crude in the international market. However, global stimuli in the petroleum industry brought about a fortuitous period for the economy of the country. Consequently, this same forces of globalization would strike again and kick-start an economic downturn due to fallen oil prices. It’s impact was felt in the Nigerian economy from the 1980s, stretching into the 1990s. It is a prominent feature in a global and interconnected economy and Nigeria was not immune to it. Africa’s post independence response to interdependence, particularly Nigeria’s, gave rise to protectionist policies that were meant to shield the economy from foreign business interests and bring wealth back into the hands of Nigerians. What these policies were not able to do, on the other hand, is shield the Nigerian economy from the effects of global interconnectedness or the attendant volatility that characterizes it. Through civil activism and solidarity, the government was forced to enact laws and put in place policies that prioritized Nigerians and reduced the participation of foreign actors in the economy. This move was described by Ekundare as the Nigerianization of the private sector. Some of the measures taken include: 1. Immigration Act of 1963 (which put a tight regulation on the ownership and operation of businesses in Nigeria by foreigners). 2. Prohibition on the importation of certain items. 3. 1972 Decree No. 4. (Nigerian Enterprises Promotion Decree) – These ensured that certain kinds of enterprise could only be established and operated by Nigerians only. A provision in the decree made it punishable by fine, imprisonment, or both if an individual was found guilty of trying to circumvent this law. D. STURCTURAL ADJUSTMENT PROGRAM – NEOCOLONIZATION? After the first republic, led by President Nnamdi Azikiwe, was truncated by a military coup d’état in 1966, the military took over and presided over the affairs of the country in a dictatorial fashion. According to Falola, “Throughout the First Republic, the country could not resolve the contradictions in a neo¬colonial economy that was foreign oriented and affected by changes in the international economic system.” As stated before, the First republic inherited a weak economy from the British and throughout its tenure, first republic leaders were unable to provide a solution to this problem. The second republic was presided over by Alhaji Shehu Shagari from 1979 to 1983. After failing to win 25% of the votes cast in two-thirds of the states as required by law, he was still declared winner and the democratically elected president of Nigeria through judicial loopholes and strong backing of the military. This was probably one of the most fortunate administrations, post independence. At the same time, it was careless and nonchalant in the approach with which it handled the economy in the midst of increased oil revenue. It squandered the opportunity for economic development and raising the standard of living. In an account by Falola, the government failed to keep the promise it made to diversify the economy. Rather than eliminate inherited problems from previous regimes, they added more woes to the economic outlook of the country. Personal aggrandizement and unhealthy amassing of wealth for personal use by party members and their cronies marred this administration. Nigeria’s transition to its third republic was botched by the then military dictator, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, who superintended over it. Babangida may have been described as an astute, ambitious, evil genius, but to ignore the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) that he heralded and implemented in the country is to ignore the significant contribution he made to the liberalization and exposure of the Nigerian economy to functional globalization practices, despite the massive failure that greeted it. He was the first to attempt the liberalization of the Nigerian economy. Scholars like Mohammed Nurudeen Akinwunmi-Othman captured Babangida’s contribution when he noted that: "The economic depression of the early 1980s, coupled with the widespread structural changes within the economy, necessitated a shift in trade-policy outlook that accompanied the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) of 1986. From an exclusive ‘inward-looking’ posture, Nigeria’s trade policy became more ‘outward-oriented’. This was mainly as a means of diversifying Nigeria’s productive base in order to reduce the exclusive dependence on the oil sector and on imports." In the face of a declining economy, rising overhead costs, high unemployment rate, and the country’s inability to sustain payments for the maintenance of its infrastructures, Babangida turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and welcomed a partial implementation of SAP. Nigerians were widely suspicious of the IMF and believed the organization to be an imperialist front for the likes of its erstwhile colonial masters. Notwithstanding, Babangida attempted to pacify Nigerians by agreeing to implement the practices of the program only, without the loan that accompanies it. The conceptualization and implementation of SAP would require government to exert limited control over the economy and encourage massive private sector control. The economy was going to diversify by encouraging a productive, rather than a consumerist economy. Government would pursue opportunities that favor the elimination of inflationary growth and cease the overvaluation of the local currency. Budget deficits were to be eliminated and a new tariff regime was to be implemented. In the executive summary of the World Bank document that contains details of this program, it was hailed as a success and all blames for the failures that accompanied the program were blamed on the collapse of international oil prices, difficulties in implementation, overspending, and “erratic microeconomic environment.” The report noted how unpopular SAP was among Nigerians and recommended that Nigerians be prepared to make sacrifices in the future for the program to be fully successful . SAP, as implemented by IMF and the World Bank prioritized the growth and expansion of the economy above the suffering and dignity of the people it was supposed to help. Moreover, as has been established, Nigerians were not particularly ignorant of whose interests these policies actually serve- MNCs. This conjures up dark images of colonization and slavery, hence the wide rejection of the policy. Its subsequent failure either elicits the sentiments expressed by the World Bank or the incompatibility of such policies with the Nigerian people and the economy as a whole. Falola captures the condition of the economy and the Nigerian people as a result of SAP thus: "It was to lead to a disaster of unimaginable proportions for the economy, enormous suffering to the people, widespread protests, and state violence. While relations with external creditors improved, SAP weakened the country’s foreign policy, added to its external debts, and ensured capital flight. Each year the government touted the gains of SAP and promised the public that the end of their pain was in sight… These policies failed entirely to correct the county’s massive economic ills. Two years after implementation the government began to waver, and by 1991, only its most ardent supporters still found merit in the program. Eventually, the economic reform collapsed, although the government refused to admit it. SAP caused the devaluation of the Naira. For a currency that had been strong for years, devaluation was a great economic shock. It generated a great decline in the standard of living as the cost of food, housing, transportation, and other necessities increased to an unbearable level. Devaluation increased the cost of all imported items, with the result that cars, spare parts, machines, and other items became unaffordable to the middle class. When the government increased the cost of petroleum products, the rate of inflation multiplied ten¬fold, creating untold hardship. The decline in living standards devastated both the poor and the middle class. Local industries suffered from limited access to foreign currency while debt added to the country’s dependence. Professionals left the country in thousands, migrating to the West and elsewhere, with the result that shortages of personnel in all leading occupations became acute. Anti-SAP protests degenerated into riots, leading to long closures of institutions of higher learning." E. SINCE 1999: RETURN TO DEMOCRACY AND SWEEPING ECONOMIC REFORMS In 1999, General Abdulsalami Abubakar oversaw a credible transition program that returned Nigeria to democracy- the fourth republic. General Olusegun Obasanjo, a former military president of Nigeria from 1976 to 1979, emerged as the democratically elected president of Nigeria. He went on to serve two terms in office from 1999 to 2003 and 2003 to 2006. The Obasanjo administration was not bereft of its fair share of crisis. A number of factors presented immediate challenges, such as sovereign political uncertainty, increased marginalization cry in the south east, continued quest to grab power by the north, a calamitous economy, falling oil prices and increased ethnic sentiments. These factors, especially those that are ethnic related, would have a far reaching effect on the performance of this government and that of future administrations. Yet, this administration still managed to go about major economic reforms that repositioned the country for business and global interconnectedness. The National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS) program was introduced in 2004 to focus on macroeconomic, structural, institutional and governance reforms. An important factor to note here was that the Obasanjo administration had figured out the enormous impact of the forces of globalization and how they affect the running of government and their consequent impact on the living standard of people. Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, a former minister of finance in this administration, and Philip Osafo-Kwaako noted that, “A major challenge for the Nigerian economy was its macroeconomic volatility driven largely by external terms of trade shocks and the country’s large reliance on oil export earnings.” An indication that Nigeria, like other countries was not immune to the activities of a globalized world. The macroeconomic reforms were meant to mitigate against such external shock. Because of Nigeria’s over-dependence on oil revenue, all government spending is based off of the price of oil. This had serious effects on both government spending, ability to start, sustain, and complete capital projects and private investments. The NEEDS program was designed as a response for countering the aftershocks of a globalization induced volatility. Dr. Okonjo-Iweala, is one of the most decorated members of the Obasanjo administration. A former director at the World Bank, who was named one of Fortune magazine’s 50 greatest world leaders in 2015. Forbes picked her for five consecutive years as one of the world’s 100 most influential people. Okonjo-Iweala is credited with managing the Nigerian economy as well as being the brain behind major reforms under the Obasanjo administration. This is indeed a woman with a global portfolio and vast in the programs that institutions such as the IMF and World Bank- which she worked for- use in managing and helping the economies of developing countries get out of poverty. The question of the true intent of such IMF and World Bank led programs is a subject that has generated different controversies and continues to be suspect even today. A survey of different countries, where such programs have been implemented, elicits the imposition of austerity measures that have direct negative impacts on human dignity. Parenti is quite resolute in his criticism of SAP. According to him, small nations are forced into granting concessions and tax breaks that favor MNCs at the expense of local enterprise, who usually go out of business as a result. The debtor nations sell off their companies at insignificant prices in the name of privatization to transnational companies, while being forced to reduce subsidies. In light of a previously failed implementation of SAP in the 80s, Okonjo-Iweala, was careful to structure these new reforms by rebranding its name, components, and implementation. For instance, privatization was a major component of SAP, this time around, it was only one of the many parts of the reform but it did not exclude the selling off of public companies to powerful international corporations at the expense of small and thriving enterprises. Under NEEDS, the government privatized about 116 public enterprises between 1999 and 2006. The power sector regulator, formerly known as the National Electric Power Authority (NEPA), was unbundled into three major arms, production, transmission, and distribution. The parent company was later rebranded as the Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN). Other sectors of the economy that were affected by the privatization exercise include petrochemical, insurance, hotel, telecommunications, and aluminum. The second component of the privatization exercise is deregulation. In truth, as a result of the deregulation of some sectors of the economy, visible improvements were witnessed. For instance, the deregulation of the telecom sector lead to the increase of telephone lines from 500,000 to 32 million mobile lines in 2007. At first, access to mobile phones and mobile lines cost a fortune for Nigerians. With increased economic diversification and with some record of success in the deregulation and liberalization of different sectors of the economy, the costs of commodities were driven down by competition. Now, access to phones and the internet increased significantly fostering a more interconnected Nigeria to the rest of the world. World Bank data shows that the number of Nigerians using the internet moved from 0% in 1999 to 78% in 2014. Financial reforms in the banking sectors fast-tracked the availability of credit to private sector investors and facilitated international transactions. Import tariffs became liberalized with the adoption of an Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS) Common External Tariff (CET) system. The aim was to simplify tariffs and promote transparency and accountability, while giving comparative advantage to goods that Nigeria produce locally. A very significant aspect of this reform is the measure that was introduced in order to reduce volatility due to the fluctuation of oil prices. The government introduced a future-sighted oil benchmark strategy, upon which budgets were created. This strategy enabled the government to create an “Excess Crude (savings) Account” for all revenues from the sale of crude above the benchmark price. F. GLOBALIZATION, HUMAN DIGNITY AND SOLIDARITY According to David C. Korten, the deprivation of the poor is usually on the increase during periods of economic expansion and decrease during contraction. This is so because income and assets ownership favors the rich, and such policies transfers wealth to those who own properties instead of those who toil and labor. He concludes by stating that growth may not cause poverty but the policies advanced to stimulate growth does. Since 1999, government reforms in Nigeria have always been touted to have IMF and World Bank undertones. As a result, they have faced opposition from genuine Nigerians and activists who are agitating for a better lease of life for Nigerians and do not wish to experience a repeat of the woes, enormous poverty, and hardship brought on by the policies and implementation of SAP. These reforms have also attracted the irk of corrupt officials who continue to amass government wealth for themselves. Historically, Africa was plundered, milked dry and forced into a culture of consumerism. This culture would keep Africa enmeshed in a long quest for total freedom. Falola captured this sentiment succinctly when she remarked that “Political independence did not necessarily lead to economic independence.” The British structures that were put in place ensured total dependence on the colonial masters and African economic prosperity and independence was poised to suffer for many years to come. The trade cultures of Africa before contact with the West was intricate, regional, and thoroughly organized. Hence, the people prospered and lived in the midst of abundant resources and wealth. The coming of the West pushed this wealth into the hands of select merchants, thereby perpetuating poverty. Obviously this weakened the will of the people and made them more susceptible to be subdued and controlled. Pundits in the West today easily allude to many states in Africa such as Nigeria as failed states. Nigeria is ranked 14th out of 178 in the Fragile State Index. What they fail to recognize is that the present economic woes of Africa rest on the doorsteps of their colonial masters. The people of Africa were dehumanized, a necessary step that facilitated success of the colonialism and the slave trade. Parenti noted that, “Many of the countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America are rich, only the people are poor. The imperialists search out rich places, not barren ones, to plunder.” Most African countries have not fully liberated themselves from the imaginary shackles of the imperialist’s and slave master’s hold on them. The structures that perpetuated this remained long after most states gained their independence. It is carved in the laws that govern them, it is modelled in trade, fashion, religion, and day to day life. Almost all facets of life are modelled after the West. No wonder Africanists are putting up a resistance to any form of Westernization, the guise through which capitalism has been able to sweep through Africa. These systems, capitalism or democracy, are in opposition to the essential and original way of life of Africans as it was before contact with Europeans. Africans are experiencing difficulties learning the democratic ways of the West, a system that is still fraught with failures and experimentations, even in America, one of the world’s most advanced democracies. It is no surprise then that the countries at the top of the Fragile States Index are mostly from Africa, or have had one form of imperialistic activities foisted on them one time or the other. A solution is for Africans rethink and remodel their leadership, economic and cultural structures around national values and beliefs. David C. Korten puts in so clearly; “By contrast, economic systems composed of locally rooted, self-reliant economies create in each locality the political, economic, and cultural spaces within which people can find a path to the future consistent with their distinctive aspirations, history, culture, and ecosystems.” Consequently, Africa’s approach to globalization should be to first look inwards in the bid to create viable, sustainable and thriving economies. An all-inclusive approach would ensure that every aspect of life in the society has been equipped to function optimally and meet the needs of its people. The economy has always taken a dive due to the many humanitarian and socio-cultural problems that has plagued the polity. Human suffering is enhanced by the increased inequality between the poor and the rich. The poor and the downtrodden of the society are often times more affected by the devastations caused by economic downturns. Lui Hebron and John F. Stacks. Jr. concluded that, Rather than constituting a rising tide lifting all boats toward greater affluence and self-fulfillment, globalization rewards a few countries, while it deepens and intensifies the economic, political, and cultural (ethnic, linguistic, racial, or religious) divides separating the world’s poor from the world’s affluent… the economic losers far outnumber the economic winners, who comprise a small part of the entire population. Globalization is thus a pernicious process that would deepen the divisions between the rich and the poor. Fights for economic emancipation, such as those of the Niger-Delta area of Nigeria always take their toll on the poor. What is important to note here is that most of the oil companies who are drilling and spilling oil, the natural endowment of these people, are MNCs and transnational giants like Shell, Mobil, Chevron among others. Their activities in these region have not only made the cost of living so high, but the environment is highly degraded such that they cannot farm their lands or fish their waters due to oil spillage. Boko Haram, an Islamic terrorist group operating in the Northern part of the country, literally means Western education is forbidden or an abomination. This group has taken up arms in its rejection and opposition to, not just Western education, but everything Western. According to the CIA World Factbook, tens of thousands of people have been killed by this group since 2009. While some are soldiers engaged in counterinsurgency campaigns, most of their victims have been innocent civilians, including women and children. This group is unmistakably vicious and heartless. However, a rational inquiry into how their agitation started would unearth the imperialistic underworking of the West and their unmitigated influence on the sovereignty and way of life of people. It is only a matter of time before countries take into account how much they have lost and how neo-imperialist activities have kept them impoverished before they mount state sponsored agitations of their own. While it is true that the forces of globalization, whether economic or cultural, are responsible for some of this carnage, it would appear that human solidarity is stirred up in people in response to human suffering when an enforced enlightenment occurs. Hebron defined the concept of enforced enlightenment in the wake of global responses to the condition of hurricane Katrina victims, “…representations of danger in the mass media can lend the underprivileged, the marginalized and minorities a voice.” When the world is made aware of the sufferings that people go through, it tends to unite us behind a common course- our humanity. CONCLUSION It is true that the world is becoming a global village. The velocity with which technological advancements are spreading has made this even more possible. The need for a free market has positioned capitalists in an advantageous position for benefitting greatly from this interconnectedness. Historically, the intention of imperialists has always been to gain access to the resources and markets of others for free or close to nothing. This quest has bred greed and an insatiable need for control of global resources at the expense of human dignity. African countries have been on the receiving end of this debasement of human dignity. Africans have had to endure colonialism, slavery, and inherit economies that were structured to benefit external players more than its owners. The solution is not for Africa to isolate itself from the rest of the world, but to integrate with caution and on its own terms. Nigeria and African countries must rethink their role in a world that is getting increasingly interconnected. There must be a conscious effort made towards floating national programs geared towards transformation and reorientation, a program that is essentially African and yet, featuring provisions for hybridized and cosmopolitan scenarios. The aim of such a program would to promote a Pan-African cultural milieu and practices that will adapt present day life and interconnectedness to values that are ultimately African. African values teach community, high moral standards, integrity, and respect. These core African values are not compatible with true profit driven, capitalist ideals. A society that entrenches these core values would promote healthy, competitive economies where community is important rather than a system where profit is prioritized above the dignity of the individual.

Bibliography “The Economic Context of Nigeria.” Nordea. 2019. https://www.nordeatrade.com/en/explore-new-market/nigeria/economical-context. Adebayo, A. G, and Olutayo C Adesina. Globalization and Transnational Migrations: Africa and Africans in the Contemporary Global System. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2009. 2009. Accessed March 4, 2019. http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook?sid=7bfffd16-8901-4185-970d-d31f86889e1e%40pdc-v-sessmgr03&vid=0&format=EB. Akintola, Lukmon. “When Nigeria Sneezes Africa Catches A Cold.” Chronicle. November 29, 2016. Accessed April 21, 2019. https://www.chronicle.ng/2016/11/nigeria-sneezes-africa-catches-cold. Akinwunmi, M. N. Globalization and Africa's Transition to Constitutional Rule: Socio-Political Developments in Nigeria. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. Accessed May 4, 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-56035-9. Berry, Sara. Cocoa, Custom, and Socio-Economic Change in Rural Western Nigeria. Oxford Studies in African Affairs. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975. Effoduh, Jake Okechukwu. “The Economic Development of Nigeria from 1914 to 2014.” Council on African Security and Development. 2015. Accessed May 2, 2019. https://www.casade.org/economic-development-nigeria-1914-2014/#_ftn35. Ekundare, R. Olufemi. An Economic History of Nigeria, 1860-1960. New York: Africana Pub. 1973. Falola, Toyin. Economic Reforms and Modernization in Nigeria, 1945-1965. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2004. Accessed May 3, 2019. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/claremont/detail.action?docID=3120990#goto_toc _____. The History of Nigeria. Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999. Accessed May 4, 2019. Harrison, Ann E. Globalization and Poverty. Nber Conference Report. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. 2007. Accessed March 4, 2019. https://www-nber-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/papers/w12347. Held, David & Anthony McGrew, David Goldblatt & Jonathan Perraton. Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, and Culture. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1999. http://search.ebscohost.com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=127964&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Korten, David C, When Corporations Rule the World, 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif.: Berrett-Koehler, 2001. Mearsheimer, John J. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton, 2001. Mgbeahuruike, Emmanuel. “Africa Looks Up to Nigeria for a Clearer Political Vision.” Leadership. January 5, 2019, Accessed April 21, 2019, https://leadership.ng/2019/01/05/africa-looks-up-to-nigeria-for-clearer-political-vision. “Nigeria.” 2019 Index of Economic Freedom. https://www.heritage.org/index/country/nigeria. “Nigeria.” World Factbook.” Central Intelligence Agency. 2019. Accessed May 5, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.html#field-anchor-terrorism-terrorist-groups-home-based. “Nigeria”. Gallup Analytics 2019. https://analyticscampus-gallup-com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/Profiles/ Northrup, David. Trade Without Rulers: Pre-Colonial Economic Development in South-Eastern Nigeria. Oxford Studies in African Affairs. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978. Okonjo-Iweala, Ngozi. and P. Osafo-Kwaako. “Nigeria’s Economic Reforms: Progress and Challenges.” Global Economy and Development Program. Brookings Institution, Washington DC, 2007. Accessed May 5, 2019, https://www.inter-reseaux.org/IMG/pdf_Nigeria_Economic_Reforms_Okonjo_2007.pdf. Parenti, Michael. The Face of Imperialism. Boulder, CO: Paradigm, 2011. Scherer, Madeleine. “If Europe Never Colonized Africa.” Prezi. 2015. Accessed May 3, 2019 https://prezi.com/xnnsgpiam3-f/what-if-europe-never-colonized-africa/ Settles, Joshua Dwayne. "The Impact of Colonialism on African Economic Development." 1996. Trace. University of Tennessee Honors Thesis Projects. Accessed May 3, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/182. Verhoef, G. The History of Business in Africa: Complex Discontinuity to Emerging Markets, Studies in Economic History. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2017. Accessed May 2, 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-62566-9.