By Anderson Isiagu, December 2020.

INTRODUCTION Background When we observe our lives and the activities we engage in from day to day, we are able to gather quickly the things that are important and indispensable for a satisfactory and rich experience. Since the time of antiquity to present day modernism, music has continuously remained an important part of our existence and the shared experiences that unite people. Great writers and thinkers such as Aristotle, Chalcidius, Guido of Arezzo, Boethius and Augustine have written extensively about music and over time, music has continued to garner mor and more attention to this day. The practice of music may exhibit particularities from one culture to the next, but the experience is universal. As Augustine put it, the experience of music ends in hilarity, that is, satisfaction. Europeans used music extensively in ritualized worship, as can be seen in the Roman Catholic liturgy. Without a doubt, music is and has continued to be a significant component in the liturgy, it was an important figura in itself, since it was a tool that was used to experience the unseen. Medieval people and people today have a common and shared experience through music. The various parts of the Mass use music actively. Music is used for different purposes in the Mass and can be found to be exemplifying important medieval priorities such as alternatim, differencia, and contrary motion. These priorities are present and easily visible in long pieces such as the sequence and those used in offertory. In African cultures, on the other hand, music plays a significant role as much as it did in the liturgy of the church during the Medieval period. Important life events are usually marked by music in the life of an African. Events such as birth, puberty, marriage, and funerals engage with and are marked by music. Music complements and facilitates these events thereby creating intense and shared experiences as a result. Ritualized ceremonies, such as initiation into age grades, puberty, coronations, and festivals engage music at intervals to mark the various stages of the process. For instance, when a young woman is being escorted to her husband’s home, the procession, however long, is punctuated by musical renditions. In some cases, this can take an elaborate shape, where huge ensembles accompany the procession. It is customary for an entire village to gather and offer sacrifices of livestock and farm produce annually to their deities and ancestors, as a way of giving thanks for a bounteous farming season, for protection, or for remembrance. A Handful of African scholars have been engaged in the attempt to draw parallels between its traditional religion and Christianity, the primary religious export of the Western world to the continent. One scholar who explored such similarities is Joseph Mulaa. He highlighted the many similarities in both belief systems and practices between the two religions. Such as the belief in a supreme being and the practice of spirituality. Mulaa advocated for increased understanding from the practitioners of both religions in order to foster tolerance and end vilification on both parts. These few instances lay a foundation to the focus of this paper. That is, a comparison of the parallels that exists between ritualized events in Africa and their European counterparts. This paper would explore the role of music, performance practice, as well as similarities, or lack of, between European offertory in the medieval period and offerings as practiced in both traditional African settings and the acculturated African church. Medieval Offertory The term offertory was not always the name for a part of the mass. It was initially used to refer to the antiphon that was sung when the faithful brought the gifts to the alter. The presentation of these gifts, bread and wine (pre-consecrated body and blood of Christ), was done with procession. The medieval period was significant, among other things, for the standardization and codification of liturgical rubrics. Some writers have suggested that Pope Gregory the Great contributed directly to the choice of antiphons that were sung during the offertory. This rite has continued to evolve in length and the choice of music since after the rubrics of Gregory the Great. Evidence from manuscripts suggest that a whole Psalm must have been sung during the presentation of the gifts, an indication of how long offertory may have lasted in the medieval period. The Offerings As mentioned before, the gifts that were brought to the altar in procession consisted of the bread and wine that would be consecrated by the priest. Did the faithful bring other items with them to be offered on the altar? What could these items have been at the time? The Bible has information that could shed more light on what could have been the nature of gifts that were offered in medieval times in addition to the bread and wine . In the book of Leviticus, there are different offerings being spelled out with details on what to offer exactly and how to offer them. Some of these offerings include burnt, peace, sacrifice, love, sin, and trespass offering. God instructs the people to bring grains, livestock for burnt offering, and meals, or fruits of the ground. In another book of the Bible, Deuteronomy Chapter 14, an instruction is given in verse two, to tithe all the yields of seed that come from the field yearly. Since the Bible has been an important source for texts that are used in cantus (Medieval sacred songs conventionally known as chants) and in the liturgy, we can easily accept this evidence concerning the nature of the items that medieval worshippers presented during offertory. The items presented for sacrifice in African cultures include animals, crops, and fully prepared meals. Apart from family altars that are found in living spaces, altars that are communally owned could be found in shrines, where people process to offer their gifts. In specific occasions, the chief priest, by divine guidance would prescribe the particular gifts to be offered as sacrifice. African Offerings – Sacrifice African traditional Religion has rituals that are parallel to some of the rites we see in the liturgy. Despite these similarities, the missionaries who brought Christianity to Africa mostly rejected the way of life of indigenous African people and their way of worship. Their musical instruments and gifts, animals, food items, clothing, and essential items were not welcomed because they were associated with Pagan worship. This association has been criticized by African scholars, who are sustaining a campaign against the labelling and vilification of African traditional practices by Western scholars. These scholars have used terms like animism, paganism, magic, or ancestral worship to describe the mode by which Africans experience the divine. For instance, reincarnation is a popular concept in African traditional worship, and parallels exist in Western civilization as can be gleaned from Aristotle’s concept of propietas und perfectiones. This concept posits that there has to be a property innate, or present inside us that can be perfected with work and efforts. Aristotle, a Greek philosopher and completely separated from the African culture seems to be echoing an important component of African traditional religion, which says that our ancestors bestow upon us, innate characteristics and gifts. Usually, it is believed that each child is a reincarnation of an ancestor, or a grandfather or mother and are supposedly blessed with the gifts that such ancestors possessed when they lived. Plato, in the Phaedo also alluded to this important concept of properties that are deposited in us and can be perfected.

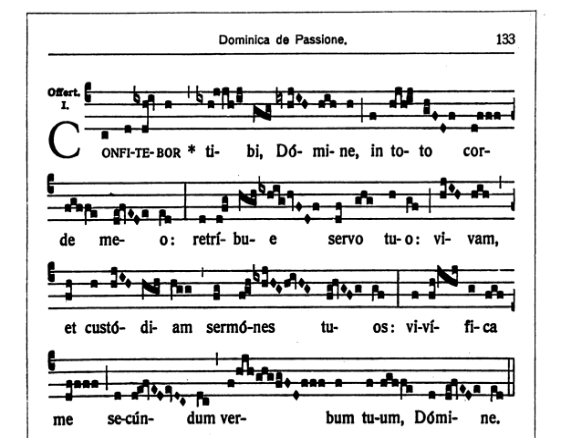

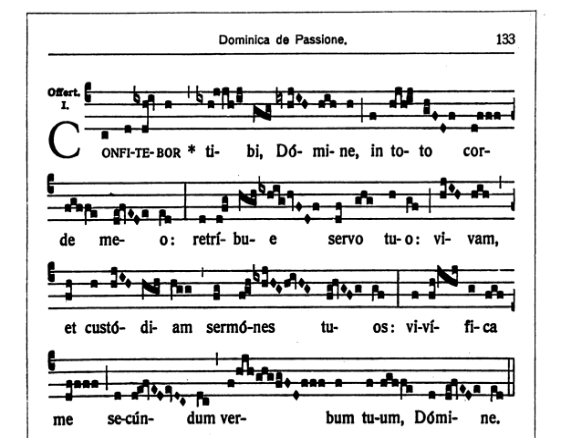

Translation I will give thanks to you, O Lord, with my whole heart: Keep me according to your word. The Music The music used in the liturgy for different seasons and solemnities are collated in the Graduale Romanum. The Offertoriale Triplex is a single collection dedicated only to offertories and it contains additional versicles that are not quoted in the Graduale. Various editions exist that have a variety of versicles in them. Some examples are Offertoriale Triplex cum Versiculis edited by Karl Ott and Rupert Fischer from 1985 and Offertoriale Triplex by Monks of Solesme. How long did offertory last during this time? Are we to investigate this by comparing it to the duration of offertory today? Or are there indications that length is relative and unique in contrast to present day? Obviously, based on current trends and as a good scholarly practice, we must not impose our circumstances upon periods, or worldviews that are different from ours. With these in mind, one could arrival at a conclusion that the times are different and, when we consider all the technological advancement of today as well as the many ways our attention is courted, the medieval mind was most definitely at rest. Hence, they could have been able to spend longer time on the liturgy. The very nature of the offertory antiphons themselves and the performance practice that inculcated versicles tend to lend a point to the validity of a longer offertory. These versicles are added in addition to the repetendum, or refrain, a small portions of the antiphon that is repeated. The text setting featured in the offertory include both neumatic and melismatic modes. A study of the manuscript of the offertory from Passion Sunday shows the interplay of these two text settings. The opening text (confitebor) is neumatic, except for the first two syllables which are syllabic. The melody written here using the C clef, expresses the 7th mode that combines both the C and the F hexachords. The presence of Bb at the beginning of the manuscript is an indication of the accommodation of the mi contra fa relationship of the F hexachord. This is later cancelled by a natural sign to indicate C hexachord. From the outset, we can deduce a major difference in the two cultures in question, one has a written and well documented repertory while the other depended on oral traditions. The West is characterized by a figura of music notation that is visible, while African cultures are replete with a figura of unseen cultural and musical practices. Through visible paraphernalia such as shrines and carved figures, most African cultures are able to experience unseen forces. Repetition is a common performance practice and length is an important factor because the music has to be repeated over and again until significant points of the ritual or rite is reached. When we consider the text of the offertory above, it bears no semblance to gifts. Consider a typical text that is sung in among the Yoruba of Western Nigeria in rituals that involve offerings to the divine; Gb’ebo wa. This text literally translates to accept our offering or sacrifice. Typically, the songs that are performed are usually pleas to the divine to accept the gifts and bless the people. However, songs that are not related to offerings are used as well for celebrations that follow the end of the rite. Conclusion The many parallels that exist between two cultures may not be fully covered in article like this one. No doubt, as many as these parallels may be, so also are the differences. Afterall, using a medieval music priority as a guide, differencia is an important concept. It affirms that differences are important and with it comes alternatim. Parts of the mass alternate between each other just as chunks inside a particular offertory alternate with a repetendum. Therefore, parallels will always alternate with differences and particularity will always alternate with universality. The conclusion is that studies of the African culture has not been carried out with complete assimilation or inculturation. Such studies, or even the practices of the missionaries were approached in from a perspective that was in opposition to African music and as a result failed to see where there were parallels. Future studies targeted at finding such parallels and the preservation of the differences between both cultures will be a welcome development that will favor the diversity and particularity aspect of music. BIBLIOGRAPHY Bonsu, Nana Osei. 2016. “African Traditional Religion: An Examination of Terminologies Used for Describing the Indigenous Faith of African People, Using an Afrocentric Paradigm.” Journal of Pan African Studies 9 (9): 108–21. http://search.ebscohost.com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=aph&AN=120046429&site=ehost-live&scope=site. "Offertory." In The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, edited by Cross, F. L., and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford University Press, 2005. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/acref/9780192802903.001.0001/acref-9780192802903-e-4944. Dyer, Joseph. "Offertory." Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 16 Dec. 2020. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000020272. Graduale Romanum Juxta Ritum Sacrosanctae Romanae Ecclesiae, Cum Cantu Paul V. Jussu Reformato (version Editio tertia.). Editio tertiaed. Mechliniae: Dessain, 1859. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433084113178&view=thumb&seq=6. Mulaa, Joseph Muyomi. 2014. “Rituals in the African Traditional Religions: The Cohesive Impact.” AFER 56 (4): 345–75. http://search.ebscohost.com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=lsdar&AN=ATLAn3789655&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Oury, Guy-Marie and Dominique Rigaux. "mass." In Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages: James Clarke & Co, 2002. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/acref/9780227679319.001.0001/acref-9780227679319-e-1809. Petitjean, Anne-Marie. "offertory." In Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages: James Clarke & Co, 2002. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/acref/9780227679319.001.0001/acref-9780227679319-e-2027.