By Anderson Isiagu, November 2019

INTRODUCTION Music and Religion Important musical inquiries intended to create a better understanding of a people’s culture, in any part of the world, is often approached from a variety of perspectives. Of utmost importance is the relationship between music and religion. Evidence from academic studies show proof of the interconnectedness and complementarity of both. It is a common occurrence to find music performed as a very important part of religious gatherings. Many ceremonies cannot take place without music. As we would see in the course of this paper, music has become an important tool in the attainment of an altered state of consciousness that characterizes a dhikr, or Sufi ceremony of remembrance. The interaction of music and the Whirling Dervish would be the focus of this inquiry. Music and Trance According to Andrew Shenton, “Music has great power to move the human spirit. It can mediate our relationship with God and become an integral part of religious and spiritual ceremonies. Music is customarily part of the rituals of every group of people…” Drawing from this assertion, this paper would approach the transcendental qualities of music used in Sufi Whirling in connection to the religious connotation of the practice and its aim. This paper will also recognize schools of thought that do not subscribe to the notion that music possesses any special attributes that makes it possible for a dervish to go into trance or ecstasy. In his book, Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Trance, Gilbert Rouget suggested concluded, after conducting several ethnographical studies, that no aspect of music (melody or rhythm) is directly responsible for transporting people into a trance-like state. He goes further to confirm the cultural association of music and how this helps to reinforce the conditions necessary to bring about a trance-like state that is achieved via music. Rouget explained further that the role of music is to create atmosphere, evoke processes and induce trance. First, Rouget’s position appear to be somewhat confusing. At first glance, one may not be able to ascertain his position. The question then is does music bring about trance or not. Secondly, He talked about music evoking processes. What are these processes and how are they connected to the subject of altered states? Thirdly, Rouget’s position would seem to be in direct contradiction of the Greek Doctrine of ethos, which stipulates that the rhythmic and melodic components of music have the power to affect human emotions, interact with our souls, and even cause healings to occur. This doctrine that was supported by the great thinkers of the time such as Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates, supports a profound power inherent in music to reach spiritual depths of the human soul. From this doctrine, deductions can be made as to the extent of music’s affect and if indeed, it is capable of inducing trance. Lastly, evidence from an experiment that was carried out in 1990 by Melinda Maxfield to investigate the effect of rhythmic movements on human consciousness showed that heightened drumming, the type used in shamanic rituals, was capable of leading to an altered state of consciousness. Details of this experiment were given in the second chapter of the book Music, Science, and the Rhythmic Brain. Then experiment, exposed different participants to a variety of drumming at various speeds. In the end, the results highlighted how rhythmic frequencies occurring at certain tempi transported participants into altered states of consciousness, with some having out-of-body experiences or claiming to have been visited by a presence. An important factor worth noting from this experiment is Tempo and rhythm. The tempo of the shamanic drumming that was around 240 to 270 beats per minute (BPM). In contrast to slower tempos and free rhythm, the shamanic type had the greatest spike in brain activities that were capable of inducing trance. Music and the Arab/Islamic Worldview Generally, in the Arab milieu, music pervades both sacred and secular spaces. It is a revered phenomenon in this culture and there is a shared agreement concerning the mystical, evocative and transcendental power of music to heal, to affect and influence, as well as to transport human beings into supernatural realities. This musical affect, how it makes people feel and how they react to it is called tarab. Islam is the predominant religion of the Arab world, this religion was rooted in the Middle East before spreading to the rest of the world. In contrast to the manner and extent in which other religions such, as Christianity and Buddhism for instance, have entrenched music in their sacred worship, Islam appears to be not be at par. Islam has witnessed controversies among groups of Muslims, especially some scholars, who argue against the integration of music and religion. According to Kamal Salhi, controversies have surrounded the role music should play in religion as well as the aspects of performance that should be acceptable . In fact, music is almost non-existent in sacred gatherings and rituals. While such Islamic scholars did not favor the outright use of music in Islamic ritual worship, there exist aspects of the religion that allowed for minimal musical integration. This is mostly evident in the adhan (call to prayer), salaht (prayers, carried out five times daily) and qira’at or (Qur’anic recitations). While these have the semblance of musical performances, they are not viewed from a musical perspective. In her book, The Art of Reciting the Qur’an, Kristina Nelson made a clear distinction between music and qira’at/tajwid. According to Nelson, “It is clear that the ideal recitation is conceived of as something quite different from vocal musical entertainment. But, more than that, it is not music at all. Qur'anic recitation may share a number of parameters with music, most obviously, melodic and vocal artistry, but the nature of the text and the intent of its performance require its separate and unique categorization…” Despite this minimal use of music in Islamic worship, there exist a widespread, shared belief about the power and potency of music in the Arab world. The scope of this paper is not intended to venture into the nitty-gritty of Islamic religious dogma or beliefs, nor would it attempt to delve into the hermeneutics of Sufism. Instead, this paper will examine the musical practices of Sufi orders, specifically the Mevlevi Sufi Order, the ritual where music plays a role and a look into the attributes of music that makes it a potent tool in the Sufi quest to experience the supernatural. Music and Sufism Sufism is an important religious tradition in Islam that has cultivated a remarkable mystical religious tradition that utilizes the cosmic and deep spiritual attributes of music in their expression of pure love for God. Sufis are Muslims who are given to a more mystical practice of Islam, it is simply a way of life, accessible to any of the two major sects of Islam – Sunni and Shi’i. Some of them believe in the mortification of the flesh, a life of poverty (there a those who believe in material wealth as well), love of and a special relationship with God, which is exemplified in a one of its prominent and frequent ceremonies, dhikr, which means remembrance of God. In Sufism, expressed in the dhikr, music is believed to possess an otherworldly, deep spiritual attribute that appeals to fundamental human emotions and an incredible ability to transport humans into ecstatic states. Sufism, as well as cultures around the world have sought to use these inherent transcendental qualities of music as a tool towards seeking and uniting with the Divine. As early as the 4th to 10th century CE, the practice of Sufism had been standardized and codified in the writings of al-Qushairi. In his Risala (Epistle to the Sufis), he brings attention to two distinct levels of mysticism, the maqam or station (the result of personal efforts on the journey towards God) and the hal or state (a spiritual mood that God bestows) . Sufi mystical practices consist of an individual’s earnest yearning to seek (maqam) and personally commune (hal) with God. A combination of elements are responsible for going into an altered state that facilitates communion with God. They include music, stylized dance techniques, instrumentation and the context of the ritual. “Sufi” by The Yuval Ron Ensemble At a unity concert in Thousand Oaks, California in October 2019, one after the other, the Yuval Ron Ensemble presented performances of spiritual music from the Middle East. One of them was titled “Sufi.” Sufi featured the Whirling Dervish, an event that marked the high point of the evening. From verbal accounts of the song’s history, gathered from an interview conducted with Yuval Ron, the leader of the ensemble, “Sufi” is a medley that combines several tunes. According to Ron, it is a common performance practice to combine play medleys because of how protracted whirling sessions can go. From an observer’s point of view, it would be difficult to pass off the Whirling of the Dervish as a mere performance, considering the transformation of the atmosphere as soon as the dervish got on stage. It was a transcendental, out of this world experience. Regula Qureshi summed this experience up thus; “One is more intuitive, reflecting the listener’s spiritual state, which finds expression in gestures, weeping, vocalization, and ultimately, the dance of ecstasy.” As a shared experience between the listener and the Dervish, Qureshi continues, “deeply moving experience of partaking in the expression of emotions, intense longing or even ecstatic transcendence that results from jointly hearing the meaningful spiritual verses sung with great intensity.” The medley consists of five sections: 1. Taqsim, slow, non-pulsatile exploratory introduction. 2. Dulab, short instrumental piece that precede a vocal performance. 3. Mawwal, vocal improvisation. 4. Allah hu, “God, him.” A text that is particular to Sufism. 5. La ilaha illa’llah, “there is no god but God”- stock text that has been set to different melodies in Sufism. The version of this devotional song performed by this ensemble was originally composed by an American Sufi, Pir Shabda Kahn. The song is performed by six different instruments, a vocalist and a simulated bass that played the drone. The vocalist and Oud, the leader of the ensemble, played the melodies along with Shvi (Armenian end-blown duct flute), Duduk (Armenian Oboe in D), and the Qanun, a plucked zither. The two percussion instruments used are Daff (a frame drum with jingles attached), and Dhol (large cylindrical drum).

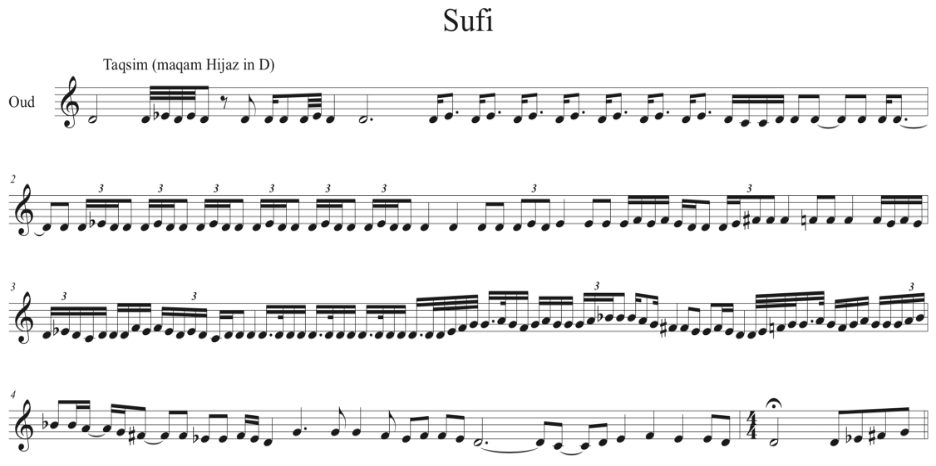

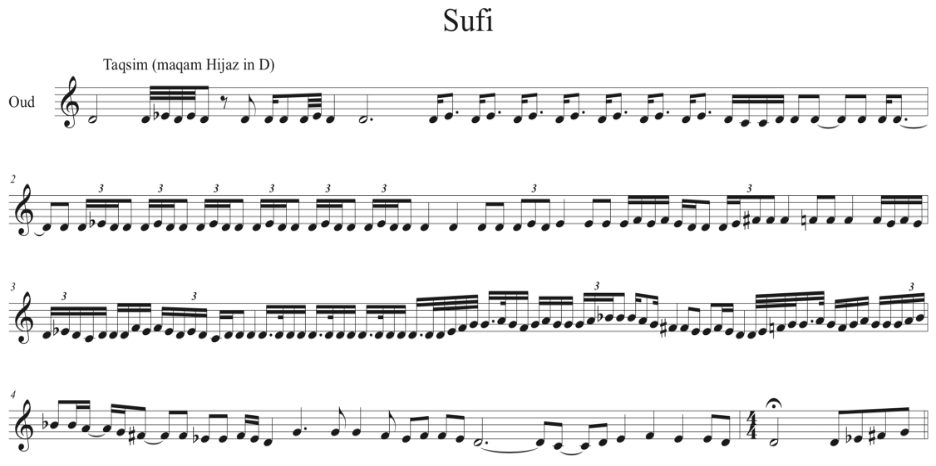

The music opens with a taqsim, a non-pulsatile instrumental introduction, that explores the core tones of maqam Hijaz built on a D tonal center on the Oud. In the background, is the long drone in D that would persist throughout the performance. Midway into the taqsim, the oud explores the note of the upper jins of the maqam introducing A and B flats a 5th and 6th above the tonic respectively. Figure 1 shows how the taqsim is rooted in a D tonal center. As the exploration unfolds, each of the principal pitches of the lower tetrachord of maqam Hijaz progressively become more prominent, all undulating and anchored around D. E flat is first exposed, followed by F sharp, then G, A and finally B flat. The last part of the taqsim features the notes of “La ilaha illa’llah,” a melody that would be heard later, before finagling coming to an end on the tonic D. An important element to note in the performance of the taqsim is how this non-pulsatile, exploratory passage helps to set the mood appropriate for a ritual of this sort. The taqsim, which is overtly, melancholic, somber, deeply reflective, creates a mood and atmosphere that is meditative and otherworldly. The drone plays a very important role in establishing this mood, akin to a feeling of floating and defiance of gravity. The effect of this mood, which is already trance-like creates an appropriate atmosphere for the spiritual quest of the Dervish.

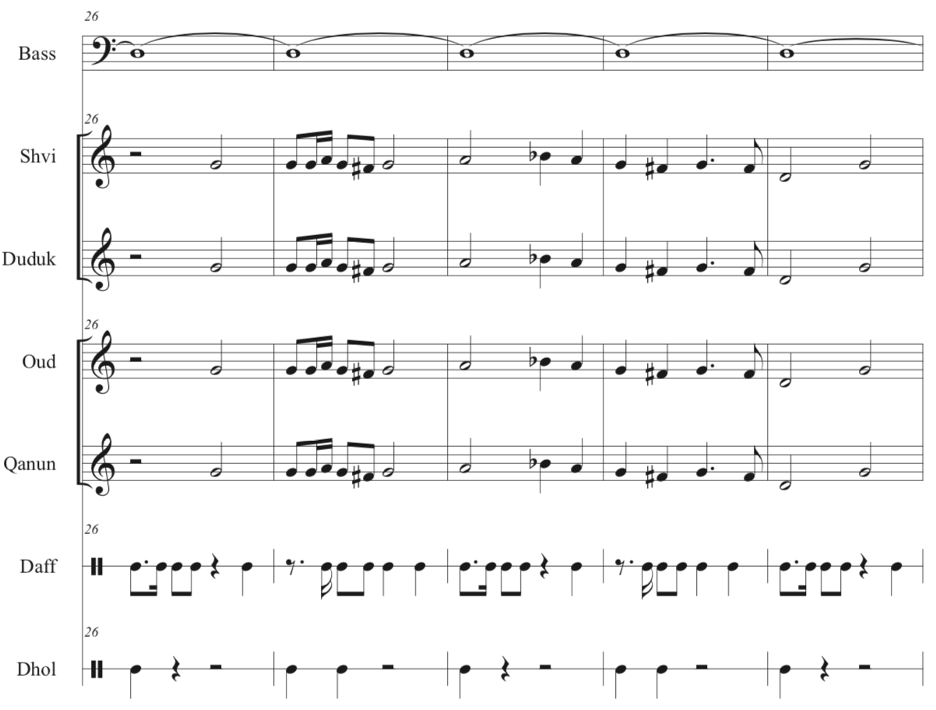

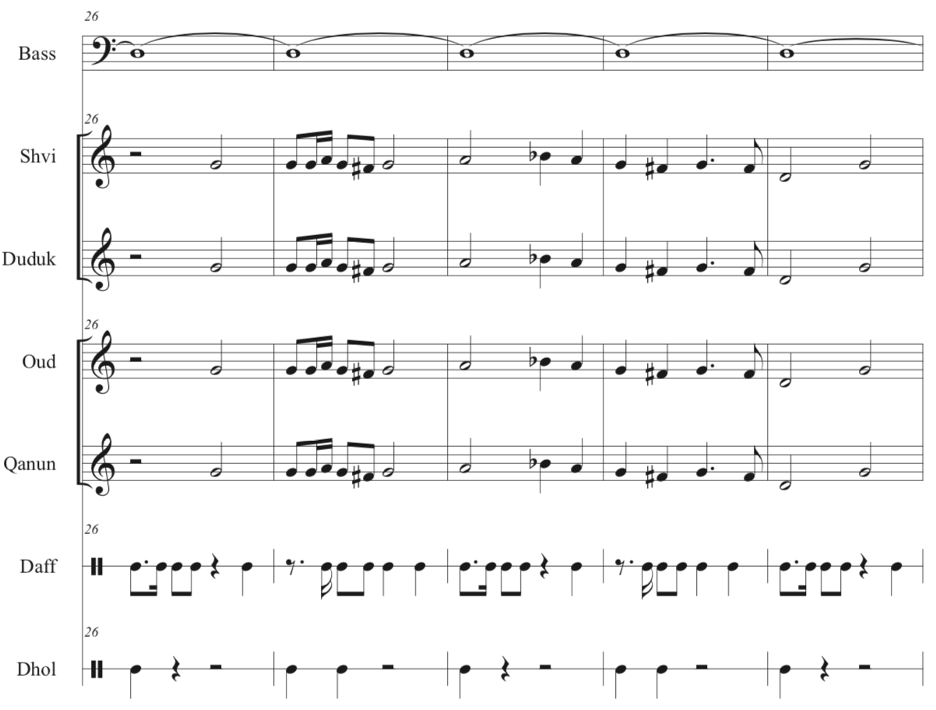

The Dulab is the beginning of the metered section of the performance. Its melody is based solely on one of the tetrachords of maqam Hijaz. It is first stated by the melodic instruments before, followed by the voice and the Shvi in m. 16. In m. 26, the melodic instruments, in a heterophony texture, introduce an interlude that explores the upper pitches of the Hijaz tetrachord. M. 36 reintroduces the voice, starting from B flat, a 6th above the tonic.

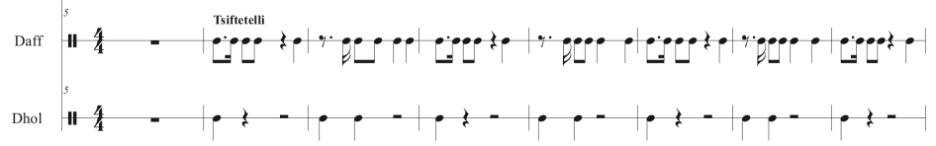

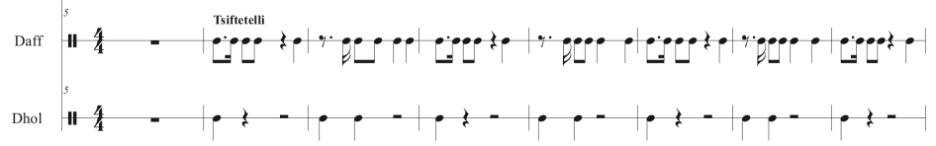

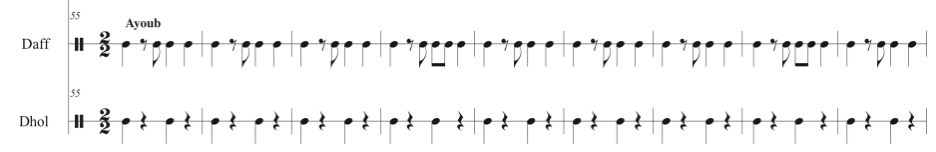

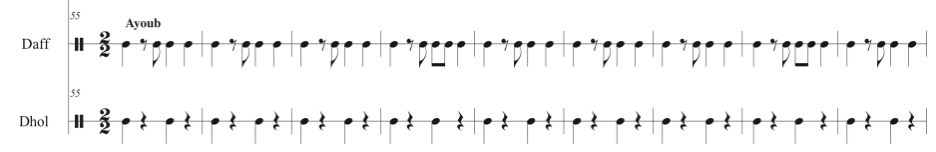

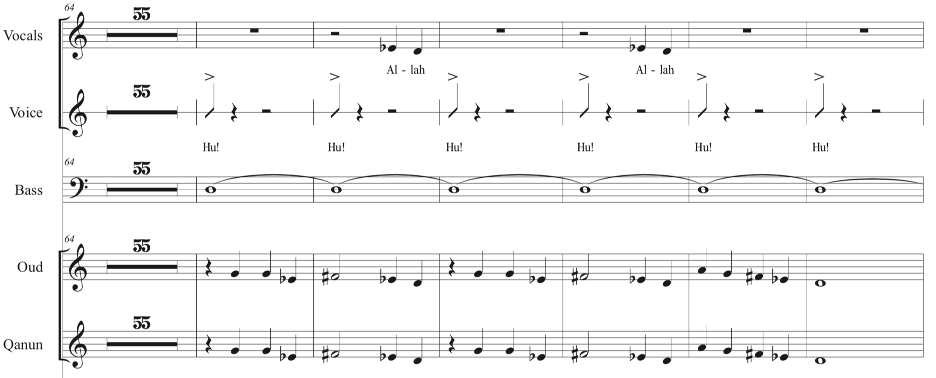

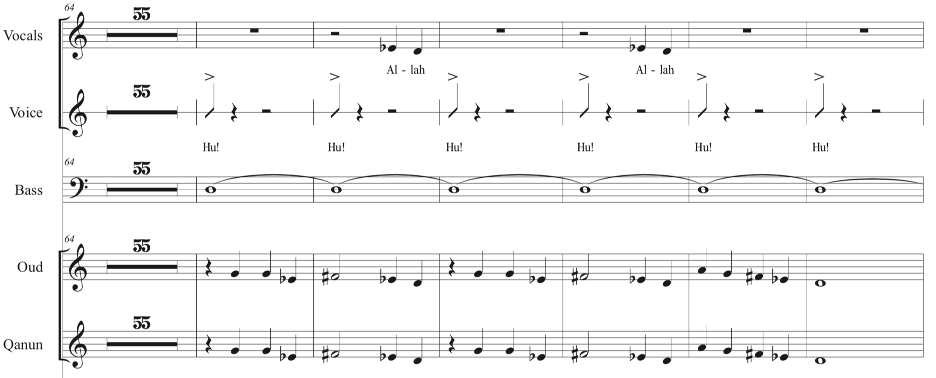

Both the vocal and the instrumental lines continue in heterophony until the music transitions into a duple time segment (m. 55) that features, as Yuval Ron describes it, a faster and more ecstatic rhythm that mimics the galloping of horses. This rhythmic pattern, described by Ron as Ayoub, is musically suitable to create the atmosphere need for a dervish to go into trance or an altered state (See fig. 5). This contrasts with the Dulab (See fig. 4), which Ron affirmed was in a rhythmic structure known as Tsiftetelli.

The interesting features of this section is comprised of improvisation by a female voice (Layali), low pitched vocal grunts that fall on the strong beat, and a tempo scheme that increases consistently. The vocal grunts, which are usually accented, resemble the syllable Hu, an important word that is known among Sufi traditions, especially during recollection rituals that use incantations to chant the name of God. Hu, derived from huwa, Arabic third-person masculine pronoun for “he,” is found in numerous Sufi melodies. Often, as is the case in this music, it is used on its own for a fricative, breathy, rhythmic re-enforcement. The layali, a vocal improvisatory passage, follows a few measures after the ayoub pattern is established. Spanning fifty-six measures, the layali is characterized by a wider range, lyrical and expressive passages, and a melodic framework that alights at the core pitches of hijaz. It is a common convention in Arabic music for a layali to be followed by a mawwal. A short responsorial phrase (a refrain), alternating between melodic instruments (Oud and Qanun) and the voice (Responding with “Allah”), precedes the entry of the mawwal melody, “Allah hu Allah” (Fig. 6). Each time, it is sung twice, then followed by the refrain. To add contrast, the call part of the refrain is played by the Duduk an octave higher, with an ornate penultimate measure. The pattern of refrain and melody continue for considerable time coupled with incremental changes in tempo.

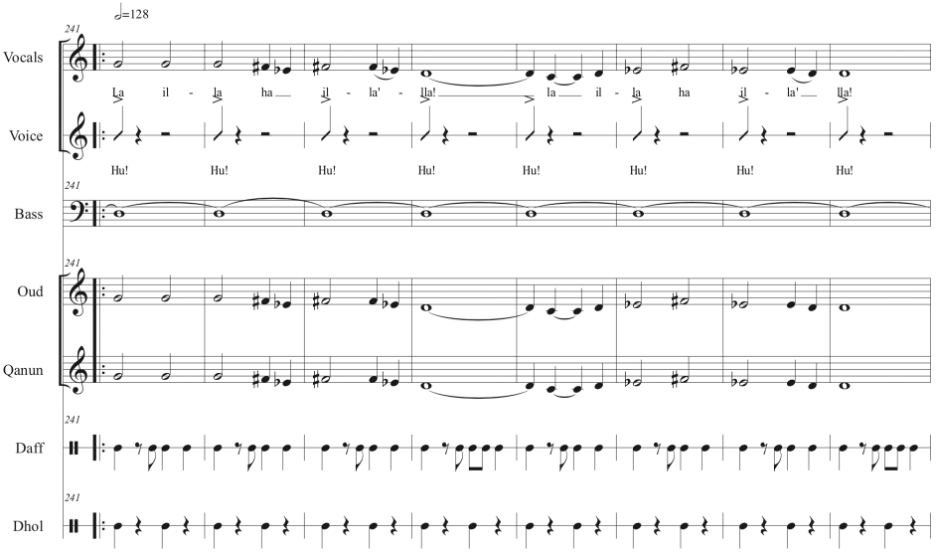

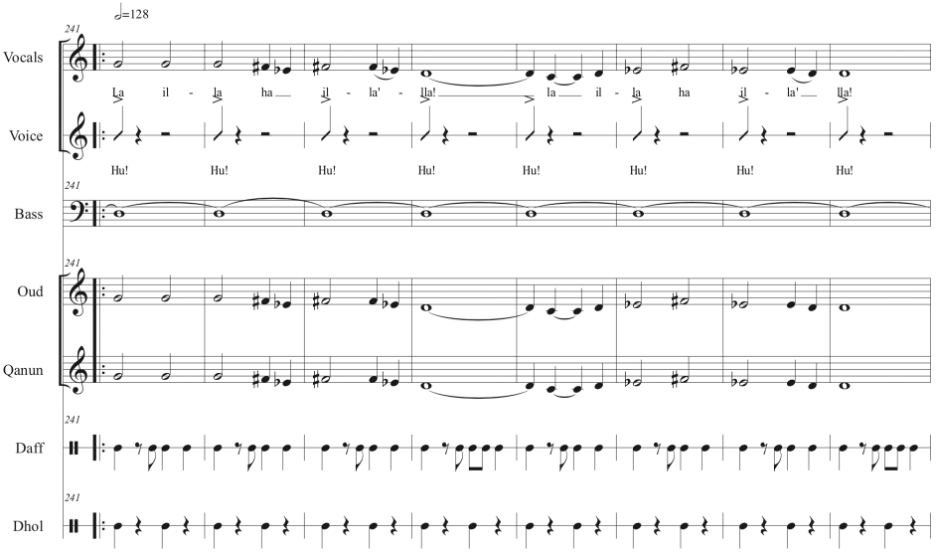

At m. 193, the music has become a lot faster (about 228 BPM), melodic instruments introduce the theme of “La ilaha illa’llah,” played twice before the voice enters to sing the same melody. The progressive increment of the tempo continues through this part of the medley, this time reaching a peak of about 259 BPM. The Shvi is now improvising freely at the top of its range from m. 242, with melodic phrase and fragments that seem to add to the ecstatic goal of the performance (Fig. 7).

Earlier on, in this paper, I tried to establish the significant role music plays in transporting people engaged in one form of ritual activity or the other into an altered state of consciousness or trance. Maxfield, in her experiment, was able to show that music or drum rhythms performed at tempos around 240 BPM and above are capable of inducing trance. At a live performance of “Sufi,” the gradual and consistent rise in the tempo attests to the level of thoughts and planning that were put into ensuring that the goal of the Dervish was attainable. According to Racy, “It is possible to find points of resemblance between the music’s overall structure and the ways in which performers work together or relate to one another professionally.” Suffice it to say that it is all structured to serve one aim only, the attainment of tarab, ecstasy, or the unity of the Dervish with God. In this performance, the Dervish makes an entry halfway into the performance of the Dulab, the slow instrumental piece. Using stylized dance moves, the dervish begins a circular move while remaining on the same spot. His hands are held just around his head level, as if abandoned in the air. A look at his demeanor reveals an abandonment, akin to a gaze with deep longing. An observer that is vast in the way of the Sufi would interpret this hollow, look of emptiness as part of the Sufi doctrine of poverty. A doctrine that seeks to remove any earthly encumbrances to the attainment of spiritual ecstasy and unity with God. Now appearing to be one with the music, he continues his dance movements, also known as whirling, in synchronicity to the music and the pulsation being articulated by the Daff and Dhol. From the melodic instruments, to the percussion, and the vocals, all these factors are working in agreement now towards creating a heightened experience for the Dervish. The Cultural context of this performance has inherent in it, qualities that aid such an experience. The microtonal embellishments of the vocalist are not just musically beautiful, but they are spiritually stimulating. According to Racy, they are “thought to embody a great deal of ecstasy.” The make-up of maqam Hijaz, characterized by an augmented second, which features prominently in the music, falls within the power of music to affect emotions as expressed in the Greek doctrine of ethos. At this point, almost appearing unconscious, yet subtly responding to every tempo change without doing anything to detract from his awestruck onlookers or the almost, equally transfixed musicians. Tempo change after the other, he continues to whirl and turn for a protracted time. As the music reaches the climax of its tempo, there is now a palpable silence and bewilderment that pervades the audience. The precision and effortless finesse of the Dervish’s moves at this point would make it difficult for any observer to believe, if they were to walk in at this point of the performance, that performer on stage is not a human sized toy that has been placed on some kind of mechanized rotor. At this point of the performance, with tempo nearing 260 BPM, it felt as if time stopped and everyone was in a peak experience, or perhaps in the presence of an insentient, otherworldly being. Without a doubt, there was an ecstatic experience in that performance venue on that night. Then, the music gradually begins to slow down, the Dervish, still in synchronicity, before finally coming to an end. The end was as spectacular as the whirling itself. The Dervish finished on the ground, bowing completely as if he lost consciousness and sense of time. Even after the music stopped, he did not just pack up and leave, he remained there for a while amid a loud silence in the hall. CONCLUSION That music possesses transformative and transcendental powers to affect people emotionally, physically, spiritually, and mentally is no doubt a fact that has been proven by so many experiments and studies. Music continues to enjoy an elevated position in most cultures of the world and their religions, as we have seen in the Sufi movement in Islam. To study the whirling dervish in the context of Sufism and religion is to unearth an important evidence of the power of music. Traditions such as this, where music underscores a deep spiritual and ecstatic association are ubiquitous. However, more studies are to be encouraged in order to determine, with certainty, that music is common to any or all transcendental experiences.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Arberry, A. J. Sufism, an Account of the Mystics of Islam. [ethical and Religious Classics of East and West. No. 2.]. London: Allen & Unwin, 1950. Baldick, Julian. Mystical Islam: An Introduction to Sufism. New York University Studies in near Eastern Civilization, No. 13. New York: New York University Press 1989. Berger, J. (Ed.), Turow, G. (Ed.). Music, Science, and the Rhythmic Brain. New York: Routledge, 2011. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.4324/9780203805299 Bohlman, Philip V. The Cambridge History of World Music. The Cambridge History of Music. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013. Lifchez, Raymond, ed. The Dervish Lodge: Architecture, Art, and Sufism in Ottoman Turkey. Comparative Studies on Muslim Societies, 10. Berkeley: University of California Press 1992. Markoff, Irene. "Introduction to Sufi Music and Ritual in Turkey." Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 29, no. 2 (1995): 157-60. http://www.jstor.org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/stable/23061989. Nettl, Bruno, Rob C. Wegman, Imogene Horsley, Michael Collins, Stewart A. Carter, Greer Garden, Robert E. Seletsky, Robert D. Levin, Will Crutchfield, John Rink, Paul Griffiths, and Barry Kernfeld. "Improvisation." Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 6 Nov. 2019. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.13738 Neubauer, Eckhard, and Veronica Doubleday. "Islamic religious music." Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 6 Nov. 2019. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000052787 Racy, Ali Jihad. Making Music in the Arab World: The Culture and Artistry of Ṭarab. Cambridge Middle East Studies, 17. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Reinhard, Kurt, Martin Stokes, and Ursula Reinhard. "Turkey." Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 6 Nov. 2019. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.44912 Ridgeon, Lloyd, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Sufism. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139087599. Rouget, Gilbert. Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession. Repr ed. Chicago, III: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1996. Salhi, Kamal. Music, Culture and Identity in the Muslim World: Performance, Politics and Piety. Routledge Advances in Middle East and Islamic Studies, 22. London: Routledge 2014. Shenton, Andrew. "Music." In Encyclopedia of Religious and Spiritual Development, edited by Elizabeth M. Dowling and W. G. Scarlett. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2006. doi: 10.4135/9781412952477.n164. Suhrawardī ʻUmar ibn Muḥammad. A Dervish Textbook from the ʻawarifu-L-Maʻarif. London: Octagon Press 1980. Touma, Habib. The Music of the Arabs. New expanded. Portland, Or.: Amadeus Press 1996. Wright, Owen, Christian Poché, and Amnon Shiloah. "Arab music." Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 6 Nov. 2019. https://doi-org.ccl.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.01139