By Dr. Anderson Isiagu

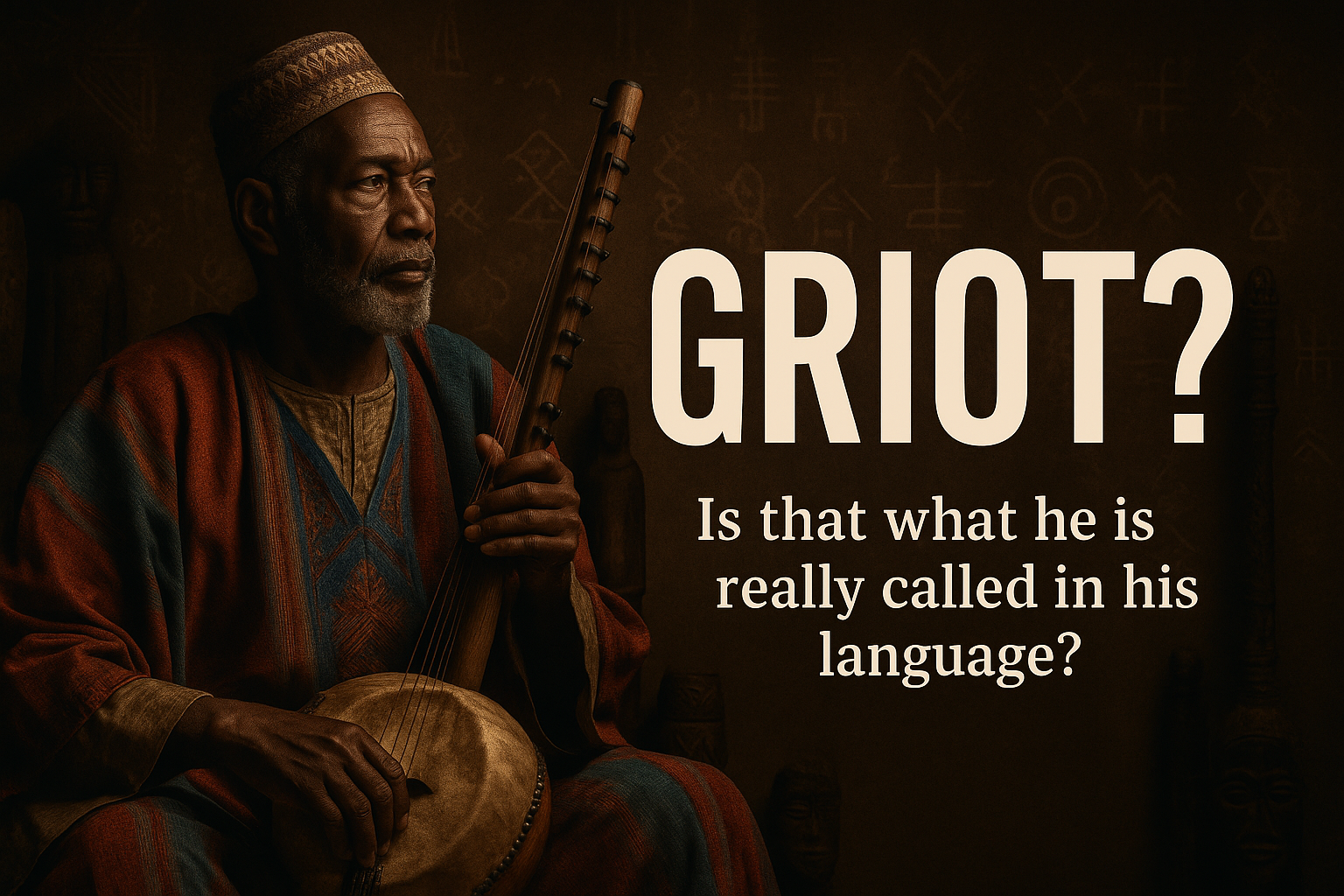

Over the course of my career as a musician, from my days as an undergrad to my graduate studies, I had to take classes and conduct one form of research or another. I have engaged in this academic exercise either for a term paper or even for personal research in my nascent scholarship. During this time, I have identified different areas of scholarship, as far as African music is concerned, that I consider part of my musical pet peeves. One of them is the word “griot.”

My pet peeves, as far as this word is concerned, started way back in my days as an undergraduate at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. I did not like the idea that African concepts were named by Europeans and that such names were being used and propagated even in African universities and educational systems. I hold the opinion that we need to stop calling every African oral historian or musician a “griot.” Why? Because the word itself is not African. This word—its history and usage in describing African folk storytellers, musicians, or genealogists—is problematic because there is no African tribe where one would find that word as an integral and essential part of its language.

Among others, “griot” has roots in the Portuguese word “criado,” which means “servant.” A popular ethnomusicologist, Eric Charry, also linked the word to Arabic qawwal due to the Arabic influence in Mali and Senegal. “Griot” can be traced to 18th-century French colonial records, where it was used by French colonial administrators in Francophone West Africa to refer to oral historians, itinerant musicians or drummers, genealogists, and spiritual leaders in the community. The colonizers, instead of clearly identifying and defining each individual whose roles are unique and different, ended up lumping all of them and designating them as griots.

In Mali, for instance, we learn about knowledge keepers who are called jeli (jeliw, pl.). Such historians, storytellers, and musicians are known by a different name, gewel, among the Wolof of Senegal. It is important to understand that African countries delineate the different roles that the French designated as griots based on their unique duties. Certainly, there are individuals who are highly talented and are able to perform all the various roles as oral historians, musicians, drummers, genealogists, or spiritual leaders and advisers. The Affa people in Enugu, Nigeria, may call such a talented person “onye akwa.” Other Igbo communities would have different names for such a person.

Furthermore, “griot” is a grossly inappropriate nomenclature to use in the same vein as a descriptive for folk musicians or praise singers, as well as highly revered title holders, among the Igbo, Yoruba, or Hausa of Nigeria. Among the Igbo, for example, the Nze na Ozo institution is a well-respected and important group in the culture, saddled with ensuring the prevalence of justice, good leadership, and morals in the community. They are clearly not praise singers but highly placed individuals in society.

There lies my pet peeve: the use of one broad stroke to paint different categories of individuals in African societies as “griot.”

The word griot found its way into academia around the 1950s and 1960s. It was widely adopted by ethnomusicologists who found it convenient to categorize oral historians, knowledge custodians, and folk storytellers in African societies. It is worth noting that this adoption was made possible because the first people who studied and attempted to theorize on African music were not Africans. Therefore, in their bid to understand African music, they inadvertently imposed European and Western musical concepts on Africa. For instance, while Western folk storytellers or itinerant musicians–known by different names across Europe, such as bards, troubadours, or minstrels–share similarities with their African counterparts, there exist significant and nuanced differences that distinguish the two traditions. Based on these nuanced differences, a word like griot that does not highlight the multiple layers and uniqueness of what is being described on the African side is insufficient and unwarranted. Clearly, in order for it to fit into their worldview, early researchers of African music and colonialists forced a broad category of individuals and custodians of culture into one word–griot.

While I did not find many African scholars who have challenged this assumption, oversimplification, and reductionism as far as the use of griot, I found an insightful take by Eric Charry, who did an extensive study of Mande music, going deep into the history of griot. According to Charry, this griot framing is inadequate and colonial (paraphrased). His work recognizes and highlights the roles of praise-singers, oral historians, and drummers. From his allusions, we can confirm that these institutions are not foreign inventions but integral elements of indigenous African life. They should not have been named using non-African terms modeled on foreign counterparts in the first place, considering their incompatibility.

Irrespective of whether there are pushbacks to the use of the word griot in describing African historians, knowledge keepers, genealogists, or musicians, the damage has already been done. This is true because the term is deeply entrenched in academic curricula all over the world, especially in Africa, where young music students do not necessarily learn what these figures are originally called in their languages but continue to perpetuate and use the imposed label because their textbooks are replete with it. Therefore, in the ongoing bid to decolonize African music, griot is one of many words whose usage we need to discontinue. We must rethink these established concepts and replace them with terminology that is more meaningful, organic, and drawn from local languages as well as cultural contexts of the communities concerned.

Here is a YouTube video of me addressing the subject: https://youtu.be/GiZzw-E089I